Like the Galapagos and the Serengeti, The Niagara Escarpment is designated as a UNESCO World Biosphere…

…Reserve and one of the world’s unique natural wonders. Photographer Mark Zelinski’s ninth book “HEART OF TURTLE ISLAND: THE NIAGARA ESCARPMENT” brings exquisite focus to the environmental treasures of the magnificent Niagara Escarpment, celebrating the ancient Indigenous cultures and modern settler communities that thrive along its rugged, curving path.

In the book preface Zelinski writes: “The Escarpment provides. For millennia, plants, birds, animals, and human enterprise have coexisted in its bounty. Its ancient limestone naturally purifies the water that runs through it. Its health offers us a reflection of our own health. The Niagara Escarpment is a living symbol of the immense scope of planetary time, and majesty, a gift to enjoy with respect and gratitude during our brief visit here on Turtle Island.

“In this new era of Reconciliation, the images and stories from “Heart Of Turtle Island: The Niagara Escarpment” will become an important document to remind Ontarians, and all Canadians, that the origins of this country began right here when, for a short time in our shared histories, we were all considered equals. The challenge we face now is not only to repair that relationship, but also to protect and preserve these beautiful and bountiful lands and waters for future generations.”

From the foreword by AFN Ontario Regional Chief, Isadore Day, Wiindawtegowinini

Click to purchase a copy of the book. Click to inquire about purchasing photographs from the book.

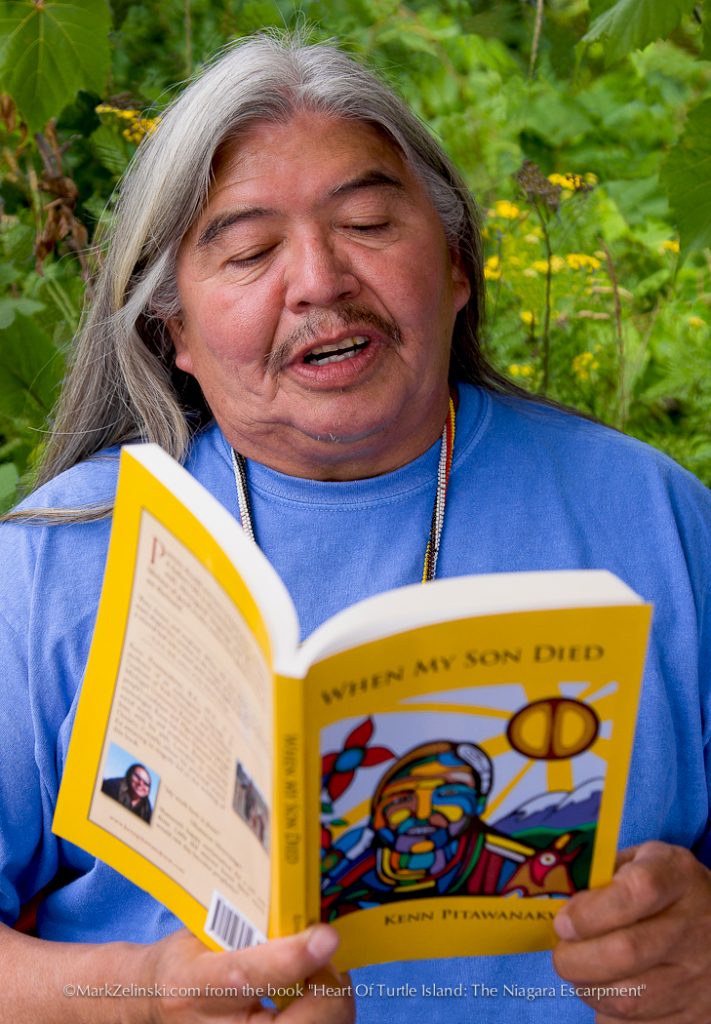

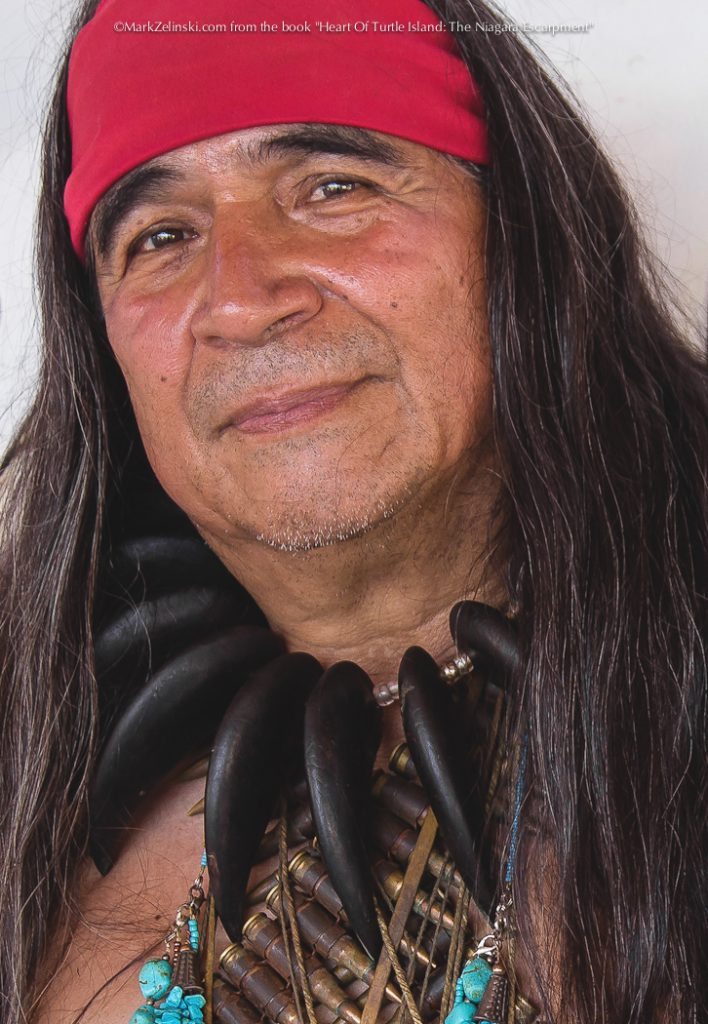

Page 40 | Wikwemikong Unceded First Nation, Manitoulin Island

Page 39 | Wikwemikong First Nation, Manitoulin Island

Page 38 | Wikwemikong Unceded First Nation, Manitoulin Island

Page 38 | Sheguiandah First Nation, Manitoulin Island

Page 37 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 37 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 37 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 36 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 35 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 35 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 35 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 34 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 34 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 34 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

Page 32 | Neyaashiinigmiing Ojibwe Territory, Ontario

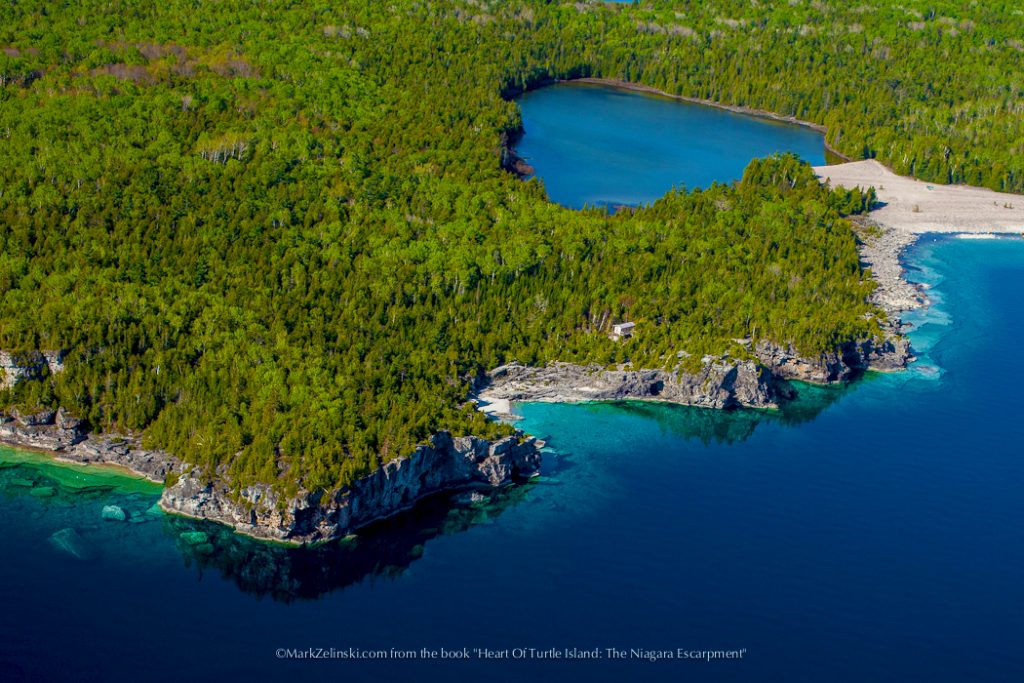

Page 31 | Bruce Peninsula National Park

Page 31 | Bruce Peninsula National Park

Page 31 | Bruce Peninsula National Park

Page 30 | Northern Bruce Peninsula

Page 30 | Bruce Peninsula National Park

Page 30 | Bruce Peninsula National Park

Page 30 | Northern Bruce Peninsula

Page 30 | Lion’s Head Peninsula

Page 29 | Beaver Valley

Page 28 | Eugenia, ON

Page 28 | Duntroon, ON

Page 28 | Mono, ON

Page 28 | Mono, ON

Page 27 | Forks of the Credit Provincial Park, Caledon ON

Page 27 | Lime Kiln Conservation Area, Limehouse ON

Page 27 | Hilton Falls Conservation Area, Milton ON

Page 27 | Crawford Lake Conservation Area, Milton ON

Page 26 | Kelso Conservation Area, Milton ON

Page 25 | Kerncliffe Park, Burlington ON

Page 25 | Dundas Valley Conservation Area, Hamilton ON

Page 25 | Bruce Trail, Waterdown ON

Page 25 | Smokey Hollow, Waterdown ON

Page 24 | Felker’s Falls Conservation Area, Stoney Creek ON

Page 23 | Niagara Glen Nature Reserve

Page 22 | Beamer Memorial Conservation Area, Grimsby

Page 22 | Louth Conservation Area, Lincoln

Page 22 | Balls Falls Conservation Area

Page 20 | Boyd Crevices, Meaford ON

Page 19 | Niagara Falls ON

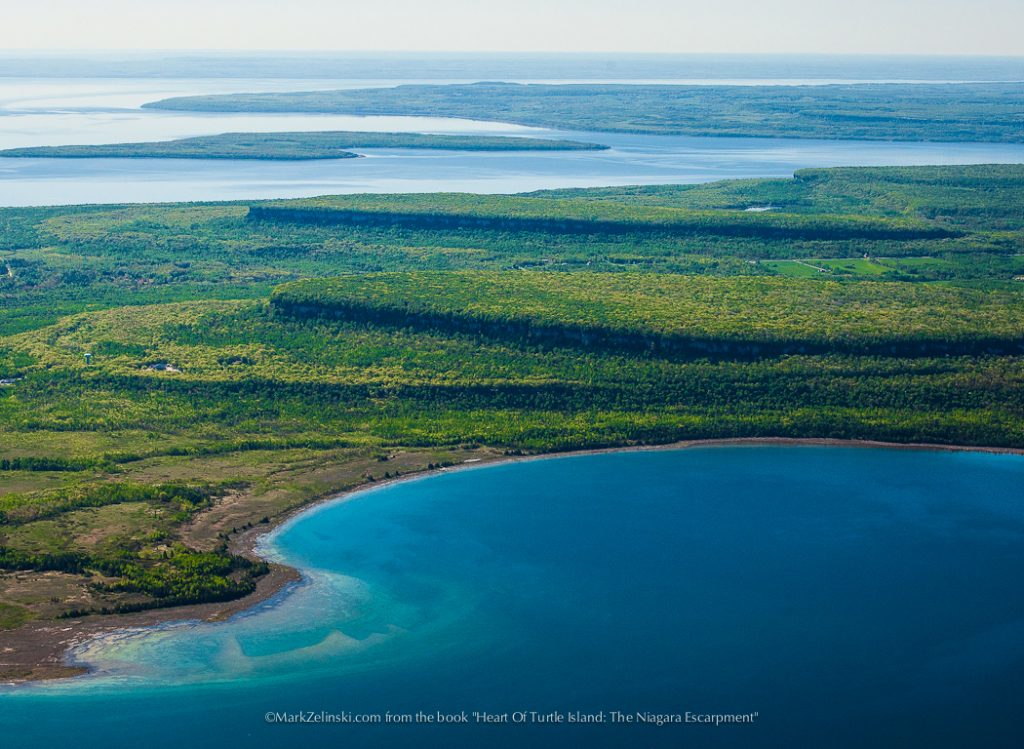

Page 18 | Manitoulin Island

Page 18 | Inglis Falls, Owen Sound ON

Page 18 | Albion Falls, Hamilton ON

Page 17 | Bruce Peninsula National Park

Page 17 | Bruce Peninsula National Park

Page 16 | Manitoulin Island

Page 16 | Silent Valley Trail, Meaford ON

Page 16 | Duntroon, Ontario

Page 15 | Bruce Peninsula

Page 15 | Bruce Peninsula National Park

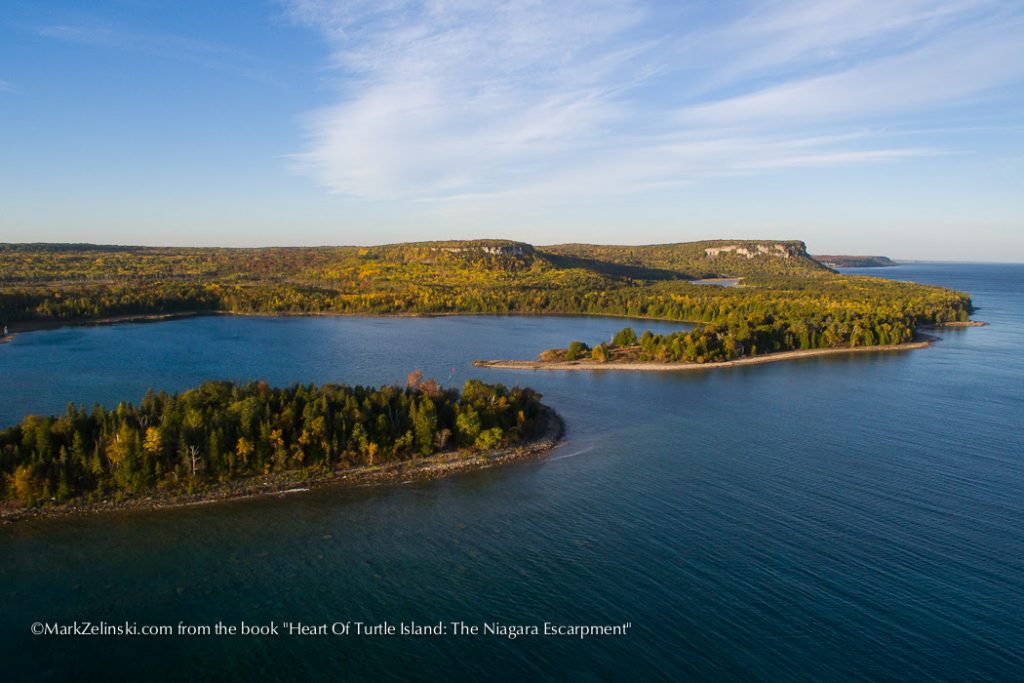

Page 15 | Wingfield Basin, Bruce Peninsula

Page 14 | Crawford Lake, Burlington ON

Page 14 |Nassagaweya Canyon, Milton ON

Page 14 | Owen Sound

Page 13 | Flowerpot Island

Page 13 | Flowerpot Island

Page 13 | Georgian Bay

Page 12 | Flowerpot Island

Page 12 | Bruce Peninsula

The Northern Bruce Peninsula’s high cliffs of the Lockport Group Strata, are formations that are more resistant to glacial ice scour and has led to exposed cliffs.

Page 12 | Flowerpot Island

The famous ‘flower pots’ of Flowerpot Island are erosion features created by the combined forces of wind ice and waves that separated the pots from the adjacent cliffs.

Page 10 | Cup And Saucer, Manitoulin Island

The Niagara Escarpment emerges from Georgian Bay as the spine of Manitoulin, ‘the Great Spirit”, Island, submerging again beneath Lake Huron The most prominent feature on Manitoulin is the cliff exposures at the “Cup and Saucer”, the highest point on the island.

Page 8 | Foreword by AFN Ontario Regional Chief Isadore Day, Wiindawtegowinini

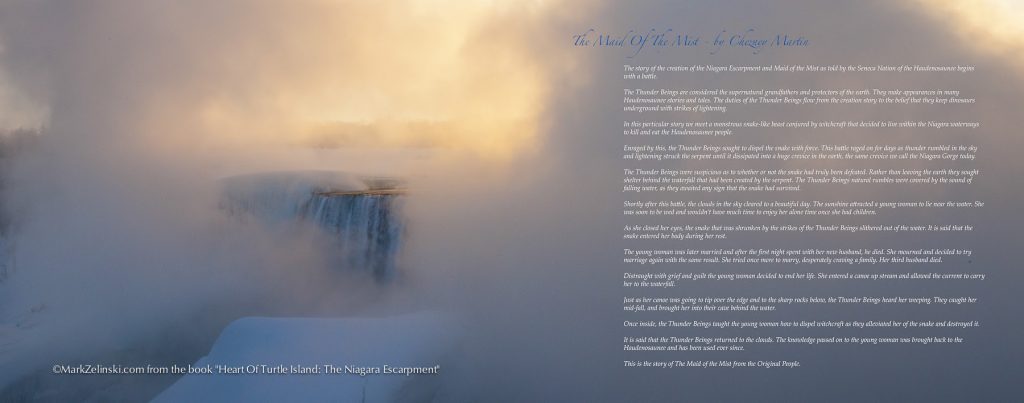

Pages 2-3 |The Maid Of The Mist – by Chezney Martin

The Thunder Beings are considered the supernatural grandfathers and protectors of the earth. They make appearances in many Haudenosaunee stories and tales. The duties of the Thunder Beings flow from the creation story to the belief that they keep dinosaurs underground with strikes of lightning.

In this particular story we meet a monstrous snake-like beast conjured by witchcraft that decided to live within the Niagara waterways to kill and eat the Haudenosaunee people.

Enraged by this, the Thunder Beings sought to dispel the snake with force. This battle raged on for days as thunder rumbled in the sky and lightning struck the serpent until it dissipated into a huge crevice in the earth, the same crevice we call the Niagara Gorge today.

The Thunder Beings were suspicious as to whether or not the snake had truly been defeated, Rather than leaving the earth they sought shelter behind the waterfall that had been created by the serpent. The Thunder Beings natural rumbles were covered by the sound of falling water, as they awaited any sign that the snake had survived.

Shortly after this battle, the clouds in the sky cleared to a beautiful day. The sunshine attracted a young woman to lie near the water. She was soon to be wed and wouldn’t have much time to enjoy her alone time once she had children.

As she closed her eyes, the snake that was shrunken by the strikes of the Thunder Beings slithered out of the water. It is said that the snake entered her body during her rest.

The young woman was later married and after the first night spent with her new husband, he died. She mourned and decided to try marriage again with the same result. She tried once more to marry, desperately craving a family. Her third husband died.

Distraught with grief and guilt the young woman decided to end her life. She entered a canoe up stream and allowed the current to carry her to the waterfall.

Just as her canoe was going to tip over the edge and to the sharp rocks below, the Thunder Beings heard her weeping. They caught her mid-fall, and brought her into their cave behind the water.

Once inside, the Thunder Beings taught the young woman how to dispel witchcraft as they alleviated her of the snake and destroyed it.

It is said that the Thunder Beings returned to the clouds. The knowledge passed on to the young woman was brought back to the Haudenosaunee and has been used ever since.

This is the story of The Maid of the Mist from the Original People.